The Origin of the Dogwatch Signal Mirror, and the Inheritance from Uncle George

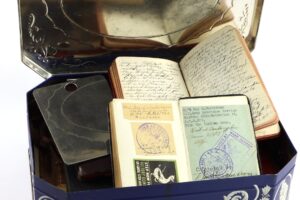

The Cookie Tin and Signal Mirror.

The Original Signal Mirror with Diaries

My dad brought the original signal mirror to a family gathering in an old cookie tin. Given what was inside, it is not surprising that the tin looked like it had been through a war. It was April, 2022, and Dad said he would bring the papers and photographs from our Great Uncle George–actually my great grand uncle–to dinner for us to see. The lid of the tin read “Huntley & Palmers Assorted Biscuits,” a British brand imported to North America. I imagine that the cookies had been consumed by my relatives at some point, and then the empty tin used as an archive.

Huntley & Palmers cookie tin

The tin is beautiful and worn. It’s an aquatic blue with white Greek figures and scrolling, and is a perfect vessel to contain family treasure. I like to think that the patina–the dents, scratches, and rust–came honestly from a host of intergenerational storage places. My favorite of these was the hayloft of Grandpa’s barn, a place where I would go as a child, searching for family treasures in steamer trunks, crates, and cardboard boxes. I’m not sure of all of the places where the Huntley & Palmers tin actually spent time, but it likely included Grandpa’s barn, our own attic, my uncle’s place in Arizona, and probably a range of closets and basements along the way. Opening it up, it had the combined scent of all of those places.

Who Was Uncle George?

George Jacob’s Tobacco Shop in Kitchener, Ontario

After my sister’s pumpkin pie was cleared from the table, my dad began taking out the treasure. First came the signal mirror, a solid, reflective piece of metal. It showed an incredible surface patina, introducing its age, that matched the appearance of the cookie tin. The mirror was put to the side of the table for later consideration as the other contents came out.

There were photos of Uncle George at Cherokee Lodge, a “resort” he and his wife Irene ran near Port Sandfield, Ontario. About a three hour drive north of Toronto, Port Sandfield was one of the small villages in the Muskoka lake district, between Lake Joseph and Lake Rosseau. The idea of a rural Ontario resort in the 1950s emphasized the value of getting away, of escaping the trappings of society, and was less intent on providing luxurious accommodations. It was a series of modest cabins they rented out for vacationers near the lake. There was a small photo album of the buildings where renters could stay, complete with text typed mostly in black, but with some red typed lettering sprinkled in for emphasis.

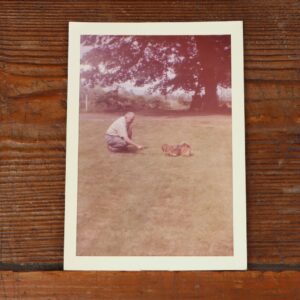

Uncle George and his dog “Little” foreshadow the Dogwatch

We also saw a photo of George on the lawn with his dog, Little, and George standing in front of his tobacco shop in Kitchener, his year round gig, in a very dapper three-piece suit. George’s personality began to emerge, and after seeing his buttoned up appearance in one context, Dad told a story that revealed a wry sense of humor. Up the road from Cherokee Lodge was a sign that pointed the to the Elgin House, a large resort not far away on Lake Joseph. George would take guests to be photographed in front of the sign, with participants carefully placed in front of the “E” and “L,” creating a record of them on their way to “Gin House.”

The Diaries from WWI France

Several very old photographs of soldiers emerged next. George served in World War I in the 228th Fusiliers of the Canadian Expeditionary Force out of North Bay, Ontario. His discharge paper showed that he served from April 1916 to April 1919, and upon leaving his body was in good health, save for an appendix scar. We could see George in his uniform with his family, with people in France, and with his unit. Alongside the military photographs were George’s papers from his voyage to France and his service there during the war. There were five leaflets from the Canadian Empress cruise line with George’s entries, and three diaries.

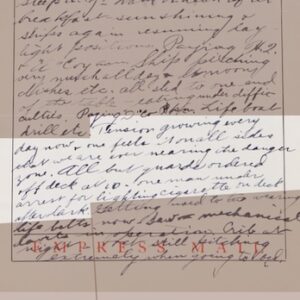

“Tension growing every day…one man under arrest for lighting a cigarette on the boat after dark.” Empress Cruise Line Diary Entry

As a person who has spent a decade or more studying diaries and notebooks–first the notebooks of living scientists and naturalists, and then the lifelong notebooks of Theodore Roosevelt–I was thrilled. One of the entries from the Empress pamphlets struck me, as it was easy to file away the information that George went to Europe by steamer without any concept of what it was like for him. His entry on the Wednesday pamphlet described them watching out for German submarines, as these were swarming the ocean trying to sink American and British crafts. I kept thinking about George’s description of watching a soldier be arrested in front of him for lighting a cigarette after dark, potentially revealing the Empress to a potential attacker who could be out in the dark ocean, watching. George was involved in some very serious business.

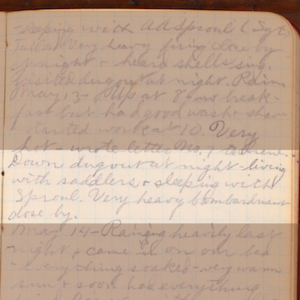

As I looked into the war journals I got a sense of who George was and what he experienced. There was the monotony and frustration of paying the troops. He missed Irene, and marked the arrival of her letters. Occasionally, bombs were dropped. They ate hardtack. On May 13, 1917, he wrote: “Had good wash + shave…down dugout at night…heavy bombardment nearby.”

“Down dugout at night…Very heavy bombardment close by.” George Jacob Diary, May 13, 1917.

The Mirror

Then our attention turned back to the signal mirror, the one he likely used for his “wash + shave.” At the top of the mirror, above the hole, was stamped “WALK HARD,” a pair of words that I assumed were a regimental slogan. I was initially struck by how substantial it was as an object. It sat well in the hand, and did not remind me of the cheap and thin camping mirrors I had seen as a child. It had quality.

The surface of the mirror reflected my face. I took some photographs on the spot, as I didn’t know how long I would actually have to see it. The tin was being passed on to my older brother, who is something of our family historian. While displaying my likeness, I was focused on how the intriguing set of small scratches and marks jumped out. I couldn’t help but wonder where each of those individual marks, each an impression recorded on steel, was made. Some surely happened in France, while

Lt. George Jacob, 228th Fusiliers

George was shaving, or dressing, while all manner of war activities were going on around. Some may have happened on a train, or on the ocean liner, while George was traveling and presenting himself to other officers. Some may also have happened as he was returning home, making sure that he looked his best for his love Irene. This must be a general principle of signal mirrors in conflicts before and after this time.

As the conversation about George wound down, I was transfixed by the mirror itself as an object of both historical significance in my family, but also one that I wanted to have in my life. It was an analog tool that could be used for shaving, travel, and be slipped into a side pocket in my bag. And if things happened to be going south while in the field, I could use it to signal for help.

Slogan “WALK HARD” on original signal mirror.

Even more, a signal mirror like this would also provide a record of my own travels in the scratches and patina that it developed. What we inherited from Uncle George was not only his papers and the records of his activities during the war. I also inherited the idea of this object, a kind of metal canvas where the marks of my own adventures could be lodged.

As the tin was packed up, headed south to Chicago with my brother, I resolved to find a way to make some mirrors myself.